That o.w.l camp bond

Through high school, I volunteered as a “sighted buddy” at O.W.L. Camp every single summer. For a week each year, I was paired with an O.W.L. camper to be his eyes, his roommate, and most importantly, his friend. At O.W.L. (Oklahomans Without Limits) Camp, campers and sighted buddies participate in a variety of activities, including archery, modified basketball, rock climbing, and kayaking. The campers have a blast, and the buddies gain a firsthand understanding of disability. It was always the best week of my summer.

Last year, I was forced out of my comfort zone when I was paired with a ten-year-old boy named David. In addition to his visual impairment, which severely restricted his field of vision, David was completely deaf. At the time, my sign language knowledge included the ASL alphabet and a simple “yes” or “no,” so I was all but useless. Mellodie King, a NewView staff member, knew tons of sign language, but David didn’t always understand what she was saying. He was also quite shy and rarely signed back. When he did try to sign to us, he used his own brand of sign language, blending real signs with various mimed gestures in a language that belonged only to him. From the beginning, communication was difficult both ways, and although David was extremely patient when I tried to convey an idea to him, it was made painfully clear to both of us that we would be on our own in the struggle to figure out how to communicate with one another.

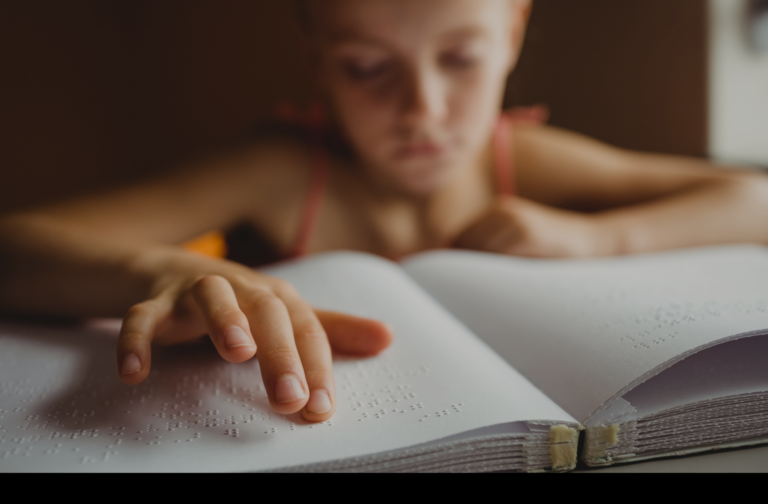

My first plan of attack was to clumsily spell out sentences with the ASL alphabet, which David knew, but he often did not understand what I was spelling and would simply shrug his shoulders in confusion. David knew I was struggling and did his best to help out. He taught me a few signs by pointing at surrounding objects and signing them, but that method of teaching was only effective for simple nouns in the immediate vicinity. The evening of the first day at camp, I requested a small dry-erase board. David was able to teach me signs in a pictionary-esque game that we played late into the night. I would draw something– an animal, an activity, or a common noun– and David would sign it for me.

We also developed a number of jokes this way. By drawing two animals with a plus sign between them, I would prompt him to draw a silly combination of the two animals, which we would then create our own sign for. That same night, I also taught David rock-paper-scissors and a similar gesture-based game called sticks. With this foundation of basic words, inside jokes, and games, David and I were able to interact much more easily than before, and the words he taught me provided important context for other signs and allowed me to fully immerse myself in his language. I absorbed all I could, and by the end of the week, David and I were able to have full conversations in sign language.

The bond we formed was unbreakable. At the camp’s closing ceremony, David and I received the “Best Buddy Pair” award. Although the award was just a decorated paper plate, handing it over to David and being able to explain it to him myself was a pleasure and a privilege. The initial struggle to communicate made our conversations even more rewarding, and those simple conversations confirmed my belief in David’s kind-hearted nature. More than anything, David showed me that in any circumstances, in the presence of any obstacles, one can remain perfectly patient and unbendingly understanding.