Where do blind people work?

Dana Branham, The Oklahoman

Unemployment for blind people is staggeringly high. NewView Oklahoma works to change that.

We are so grateful to Dana Branham and Doug Hoke with The Oklahoman for capturing our story and our mission so beautifully. To view the original article in The Oklahoman, click here.

After Hannah Kinsey graduated from college, it took her five years to land a job.

That wasn’t for lack of trying. Kinsey has been blind all her life, and she knew the daunting unemployment statistics for people who are blind or live with vision loss.

One of the biggest hurdles she faced was just getting through the online applications for job postings. Many were impossible to use with her screen reader.

“You can’t even get in the door, because I can’t fill out your application,” she said.

Today, Kinsey works with NewView Oklahoma on the nonprofit’s READable division, which works with businesses and other organizations to ensure their documents and websites are accessible for people with disabilities, including blindness.

But those five years of job searching were rough, she said.

“It makes you question, am I doing the right thing? Should I have gone a different route in school? Or did I just not apply at the right places, or could I have done more?” Kinsey said. “But it’s not a failing on my part.”

Blind people and people with low vision face significant barriers to employment: transportation difficulties, a lack of accessibility in the workplace and ignorance about their capabilities.

NewView Oklahoma, a nonprofit focused on empowering blind or low-vision people and helping them lead independent lives, is the largest employer of people who are blind or have low vision in Oklahoma.

But its leaders would be thrilled if that wasn’t the case in 10 years.

“People with vision loss or individuals who are blind are just as capable as everyone else,” said Lauren Branch, NewView’s president and CEO.

‘Where do blind people work?’

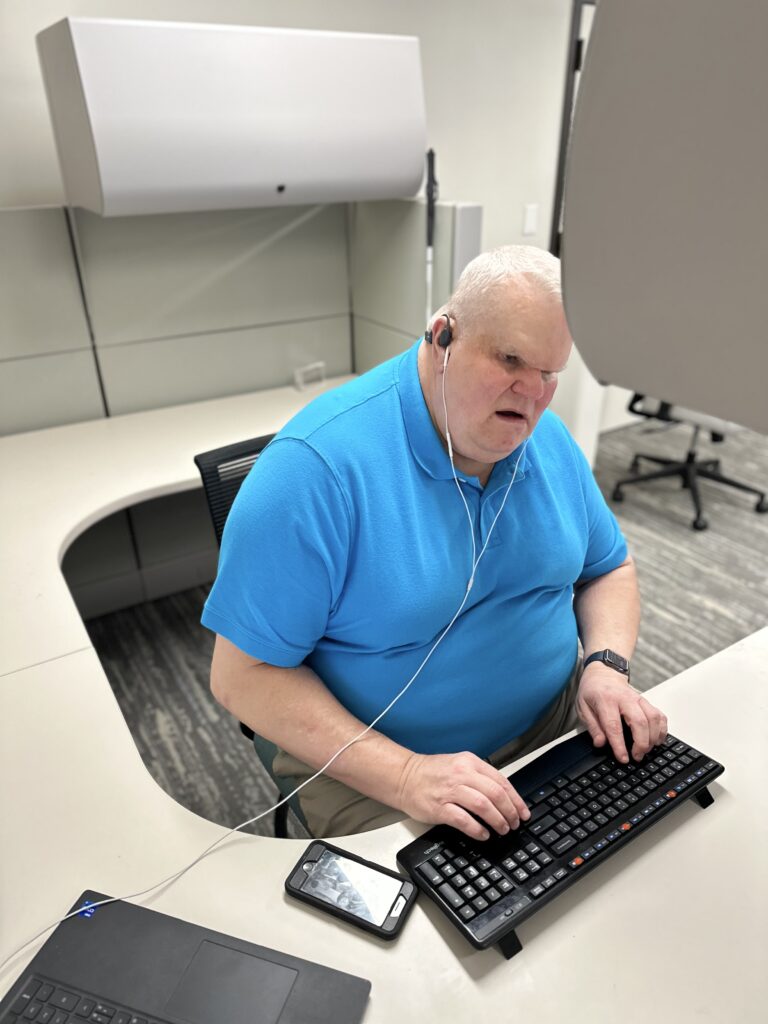

Gerald Robertson had worked in manufacturing all his life. When he lost his vision in his 40s, he wasn’t sure what was next for him.

A friend of his worked at NewView, and when the friend learned Robertson was blind, he asked if he was working.

“And I said, ‘Well, where do blind people work?’” Robertson said.

Robertson applied and got a job at NewView’s manufacturing plant, where many other blind and low vision people work, as well as people with other disabilities. The plant has raised tracks on the floor to help people navigate with canes, and brightly colored railings help people with low vision get around the space safely.

Machines in the plant have been modified to run safely in a number of ways. One, for example, requires two people to operate it, and each person has to use both of their hands to press a button for it to run — avoiding the risk of anyone’s hand getting caught in the machine.

At the NewView plant, workers make a variety of goods: They’re the sole provider of firehoses for the U.S. Forest Service. They also build first aid kits, wheel chocks for the Air Force, and other goods used across the state and country.

Robertson took training classes through NewView, relearning to type and use a computer with a screen reader.

“I don’t really know what I would have been doing had I not found NewView,” said Robertson, now a production supervisor.

In addition to employment opportunities, NewView works with blind and low vision people to teach them “how to be blind,” said Mark Ivy, who works in fundraising and development for NewView.

Ivy has retinitis pigmentosa, an eye disease that causes vision loss over time. His younger brother does, too, but his brother’s vision loss started when he was much younger.

“When I graduated high school, NewView came to my living room in Tulsa with my younger brother there, too, but mainly for me, to say, ‘Here’s what’s about to happen,’” he said. “The more vision you have with something like a degenerative eye disease, the more you get to learn and get ahead of the eight ball.”

About four years after they left his living room, his vision started deteriorating. He had to stop playing baseball and stopped driving — “things that will break you,” he said.

Ivy called NewView and started learning. But finding his first job was still tough.

“I would go in places and they would tell me … ‘Hey, there’s a lot of computer work here, a lot of Excel work — we just don’t think it’d be fair for you,’” he recalled. It wasn’t malicious, he said — people just didn’t understand.

NewView helped him get an internship working for then-Congressman James Lankford, and he held a few other positions before he landed his current role.

“I love getting to raise money for something that helped me and my blind community as well,” Ivy said.

Breaking down barriers

Most estimates put the unemployment rate for blind or low vision people somewhere around 70% — a staggering figure that represents a “very capable, untapped workforce,” said Branch, NewView’s CEO.

A number of factors contribute to that high unemployment rate, including transportation difficulties, a lack of accessibility in the workplace, and misconceptions about what kinds of jobs blind people can do.

NewView regularly invites organizations for tours and educational experiences, and the nonprofit also works with companies to help them include blind or low-vision people in their job searches. Even so, it can be difficult to break down biases, Branch said.

Sometimes, business leaders think making the necessary accommodations for blind people will be expensive, she said. Or, they might assume their jobs could only be done by sighted people.

Even well-meaning organizations can fall short when it comes to accessibility. Years ago, an employer that sought out NewView’s help in developing a candidate pool found that blind or low vision candidates faced a number of roadblocks in the application process, Branch recalled.

At first, the online application wasn’t accessible at all. Then, when that was addressed, one part of the application automatically rejected candidates without a driver’s license, she said. Once that was solved, a CAPTCHA challenge — those little tests on web pages to determine whether you’re a robot — required the candidate to identify several pictures without any accessibility features.

“It’s not the lack of capability on the individual who’s blind’s side, it’s the lack of accessibility on the employer’s side,” Branch said.